Productivity and timesheeting life – lessons in mindfulness

It’s really clear that the most precious resource we all have is time.” ~ Steve Jobs

Time is the most valuable resource we own. We cannot make it or earn more. We trade time for money, or build capital that earns money on our behalf. This “frees up” our time, inferring that our time was otherwise held captive. We don’t measure our time, but it can come as a surprise when we discover we are running out.

Facebook ads about fitness and financial management programs tell me that we are in the last week of the New Year’s resolution season. I figured it would be a good opportunity to share an experiment in timesheets and mindfulness.

The experiment

Around three years ago I conducted an experiment where I completed timesheets for every second of my day.

My relationship with timesheets had been tenuous at best. I had just finished seven years as General Manager of a 60-person digital agency where timesheets were a consistent stress point. Timesheets tend to turn people into products. I didn’t like doing doing timesheets, and disliked myself for asking others to do timesheets.

So I decided to lean into my dislike and conduct an experiment. I was curious how much time I spent in the different areas of my life. My life has always consisted of a portfolio of projects, and I wanted to see which projects were getting more of my time.

As is the way with experiments, I discovered an unexpected outcome. By forcing myself to be conscious of how I was spending my time, I became more mindful, focused, and appreciative of each moment.

The experiment ended after three months when I missed a few days, my workload increased, and the timesheeting tool I built needed more work than I was prepared to give.

Renewing the experiment

Fast forward a few years and my portfolio of projects has increased. I support multiple organisations with innovation management, work on my PhD, and have my own startup in preparation for a national tour planned for later this year.

I have used a number of techniques to keep track of things, from processes like pomodoro and bullet journals, practices like meditation, and systems like Trello and Asana. It can still get a bit of a challenge to know where my time has gone by the end of the day.

So after a 2am wake up with my mind going through my day, I decided to start the experiment again.

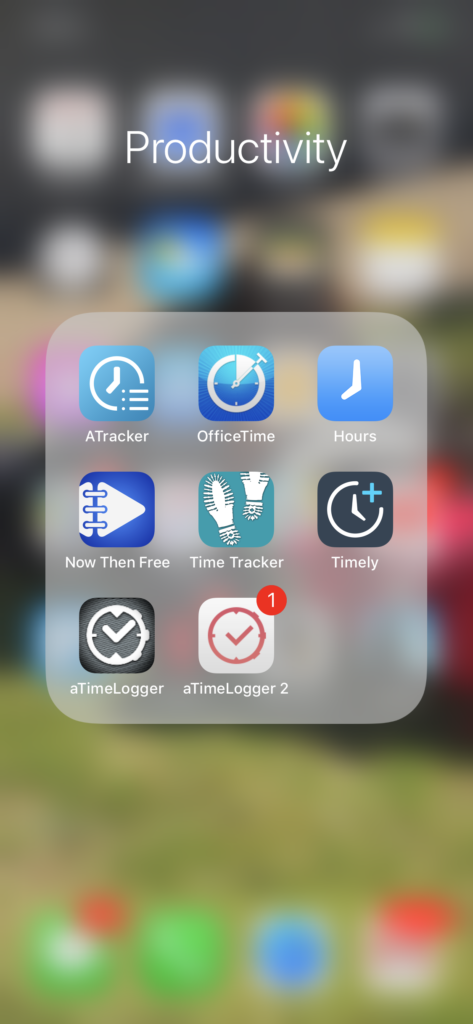

Thankfully the app explosion means that I no longer need to build my own. A quick search turned up a few tracking apps.

Three things I was looking for included:

- Easy to update and switch between tasks

- Ability to assign tasks to projects

- Ability to categorise tasks

Many of the apps are focused on billing and invoices, team tracking, and tracking tasks against client work. Some have additional features I was not interested in like GPS tracking and receipt capturing.

After spending a few minutes with each, I paid a few bucks to aTimeLogger 2. It looks like it does exactly what I need.

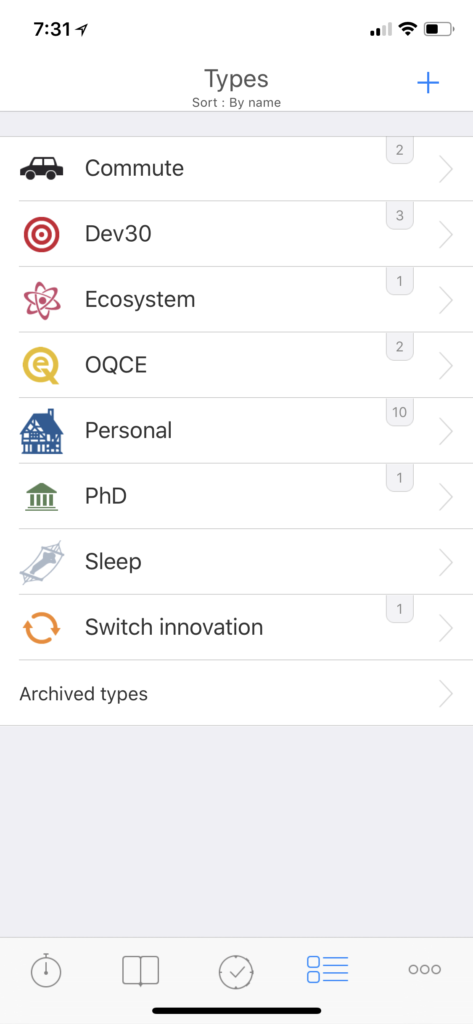

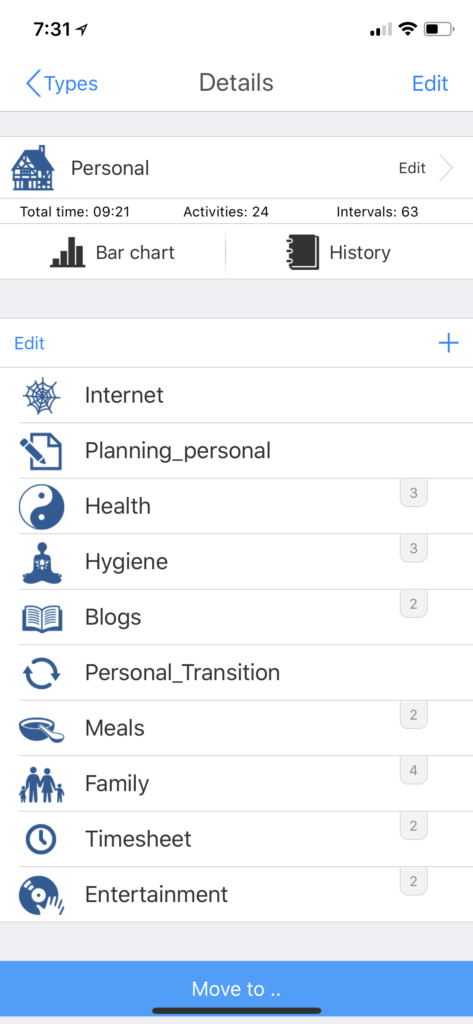

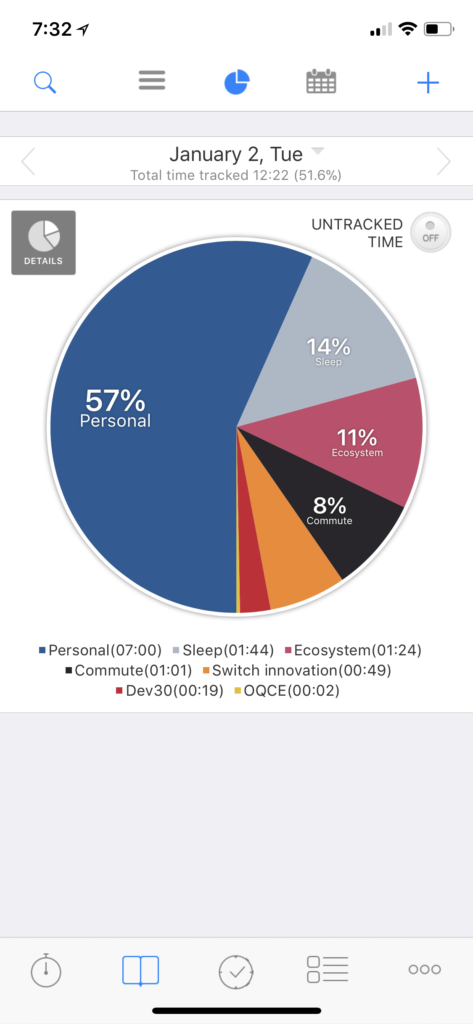

The app allows me to create groups for the different domains of my world, including my day job work with the Queensland government, support for the local ecosystem, my consultancy work with my company Swich Innovation, my startup code-named Dev30, my Phd, and Personal. I put Commute in a separate group to track transit time for each domain, and sleep is its own category to more accurately represent Personal.

Sub-groups allow for further task categorisation. Goals can also be created to allow time to go against, but I am not using that feature at the moment. Reports can be created at the group or activity level and everything can be backed up and exported.

Lessons relearned

It is early days again and I will share more after another three months. This is not something I would prescribe for everyone, and indeed have not met anyone else who has gone to this extent. Those who combine Pomodoro techniques with bullet journals come close, while others may have developed internal habits and may not need the extrinsic process.

Here’s some lessons I have re-learned so far:

It’s not that painful

Like seeing a needle at the doctor’s office, the aversion to timesheeting and being ‘tracked’ can be more painful than the actual activity. I have a task dedicated for the act of timesheeting. After a day, that task has 16 minutes against it, mostly because I was taking notes for reference about the task as reminders for follow up.

It takes setting up

I spent a total of 32 minutes setting everything up. Most of that was when I needed to create a new group or task. This will get easier as I repeat common tasks more in the future. It is worth creating unique icons and assigning colours to each group for later review.

It forces you to name your actions

The hardest part can be determining which bucket your time goes into. The process requires you to always know where you are focusing your attention. Social media notifications and emails constantly tap your attention. Office environments are prone to random conversations. The approach does not require you to not be distracted, just to be fully aware and tell yourself “This is what I am doing right now.”

Awareness without judgement for decision making

Like meditation, the purpose is not to judge what you are doing, but to be aware. Just as meditation helps you observe your thoughts, timesheeting allows you to be conscious about what you are doing. Rather than judging in the moment, it allows you to reflect after the fact to make future decisions on what is important and where you want to spend your time.

What you focus on you grow

The process exposes your priorities. If you say exercise is important, it can be confronting if you have one 10-minute workout session after a week and 90 minutes surfing the Internet. Like a form of gamification, knowing you will log the time and add to the chart can be an encouragement.

You become aware of the cost

I may think I am going to pump out a blog post a week, but by measuring I know each effort takes around two hours end to end. Looking at the true cost of commuting can help me make decisions about what else I can be doing on that commute. You can then make decisions on how you spend your time based on data rather than assumption.

It helps you delegate and scale

When I coached CEOs, I occasionally asked them to keep a time diary to identify functions where they spent their time to help identify where best to delegate. I did this myself when running Fire Station 101 to identify functions to split between Operations and Community Management. Once you see where you spend your time, it helps identify where you can get others to help so you can focus on what is core.

Measurement is not execution

Finally, measuring is not doing. Rather than the time taken to measure and even write this post, I could have progressed any number of projects are even just hung out with family. The goal is that by being more aware, it will make other activities more intentional.

Next steps

If you believe dystopian programs like Netflix’ Black Mirror to be prophecy, the practice described above is a manual approach to inevitable embedded chips and real-time recording of our lives.

We already measure so many things. We have apps to measure our food intake, our workout routines, the number of steps or breaths we take, our finances, our location, and more. We access these apps in ways that are increasingly real time, from phones to watches to glasses. Measuring our time may be the next step.

I expect to continue for another three months and see how I go. I may also incorporate a form of the practice on my innovation tour later this year, as the theme will be around measurement.

My intention in writing this is not as a prescriptive “how to” or to get anyone else to follow the practice, but to capture my thoughts in the moment. At a minimum it may help others briefly consider where they spend their most valuable resource of time.

It also helps explain why I might quickly look at my phone if you come up and chat with me. At least until I get the chip embedded.